The invention of the first home pregnancy test

Not so long ago, a pregnancy test required a visit to the doctor's office. Someone else gave you the news. Ever wonder how that changed?

5 minute read

It was just a fluke that Meg Crane even saw the rack of test tubes. They were inside Organon's main building, which housed the labs, and her workspace, as a graphic designer for the company, was in a little outbuilding. But that day she went inside and the test tubes caught her eye, so she asked what they were for.

Pregnancy tests, she was told. For doctors. It was 1967.

The idea hit her right there. "I thought, 'Oh my god, if all it took was a test tube and the right chemistry and a mirror, I could fix this up for women to do that themselves,'" she told me. "It was kind of a lightbulb moment, actually."

She approached a VP and suggested it: pregnancy tests women could do by themselves at home.

He laughed. If women could do that, the company would lose business with doctors, he said. And anyway, women wouldn't be able to manage it.

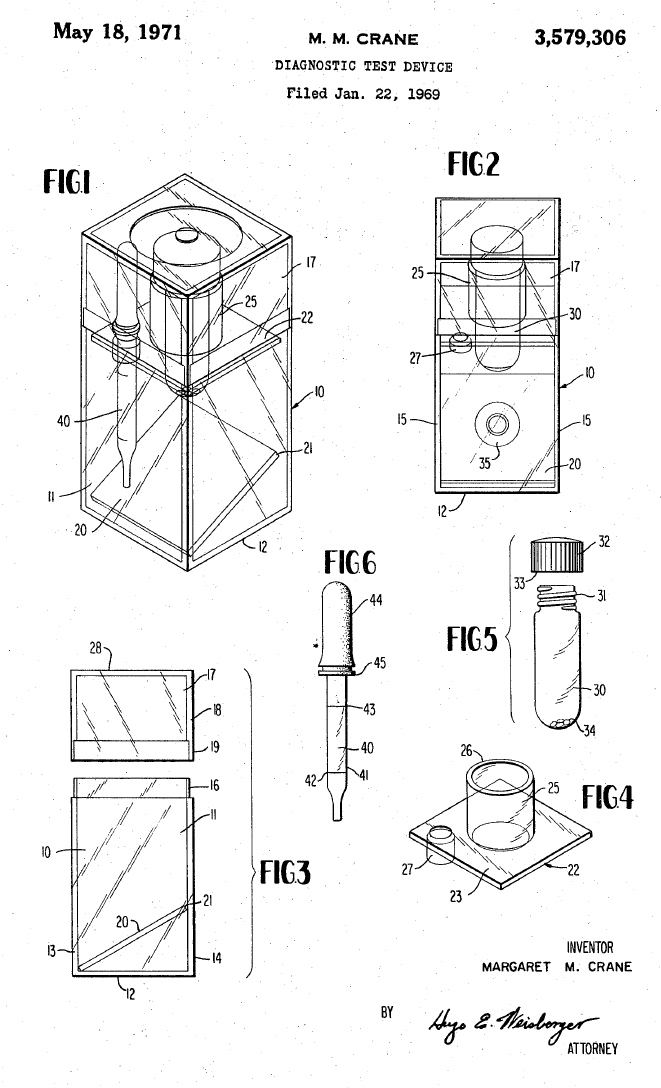

Crane was pretty sure they would. And in her spare time, she started working on a prototype. Within a month, she'd built a model test kit inside a box-shaped clear-plastic paper-clip container. She constructed a shelf with one hole for a little eye dropper and another hole for a little test tube. In the bottom, she fashioned a mirror out of mylar and placed it on an angle.

The woman would take the lid off the container and use it to collect a urine sample. Then she'd use the eye dropper to draw up a precise amount of urine and place it into the test tube. An amount of water would then be added. (The eyedropper showed how much of each was needed.) She would then seal and shake the test tube, so that the two liquids would interact with the chemicals already inside, and she'd place the test tube back into its slot and leave it completely still for two hours.

It was important not to disturb the test tube, ergo the mirror. If there was enough of the pregnancy hormone hCG in her urine, a brown-red ring of sediments would form on the bottom of the test tube, visible in the angled mirror, and the woman would know she was pregnant.

Crane went back to the VP with the prototype. It was elegant, he conceded, but it would cost a fortune to produce. And with that, her idea was dropped.

Except that it wasn't. On a visit to the parent company in the Netherlands, somebody mentioned it. The Dutch thought it was brilliant — they bankrolled a test run. Crane would not have known about any of this had it not been for the secretary who worked in the outbuilding with her, who mentioned an upcoming meeting on the subject.

Crane, uninvited, decided to attend.

"I got there early and waited for people to arrive. And executives from the company came in — all men." It turned out the company had hired some product designers — also men — to develop their own prototypes, and they now placed them on the long conference table. Crane pulled hers out too.

She'd never crashed a meeting before and wasn't sure how things would turn out. She didn't know if they'd fire her. She was in her twenties and hadn't been employed there more than a couple of years. But she was angry. "I just had to do this," she says. "There was no way I would not be going."

In the end, her prototype was favoured by the ad agency, even after her colleagues insisted it was "just something Meg came up with for talking purposes." When the company continued to insist it would be too expensive, she sourced some competitively priced plastic boxes. There was no way around it at that point, she jokes: they had to use her design.

The test market was Montreal, 1971. Its name, The Predictor.

As it happens, the ad man Organon had hired ended up as Crane's life partner, and the two of them, now running their own company, spearheaded the marketing. They went to Montreal for the campaign. She saw her product on shelves.

Not surprisingly, it was popular. But it was also controversial. Not everyone thought women should be in charge of their own pregnancies. It wasn't until 1977 that the home pregnancy test was for sale in the US.

You can imagine how rich Crane must be as the patent-holder. But now in her eighties, she still has to work to support herself. She earned nothing from her invention.

One day she'd been called to the company's main office, she says. There was a little ceremony. The company lawyers were there, pens in hand and paperwork at the ready. They wanted the patent to be in her name, they said, and they asked her to sign on the dotted line. "And stupid me, I didn't have a lawyer, or anybody else with me at the time," she says, "and I signed the papers."

"I tell young people today, 'Listen, if you're in a situation where you've got something valuable, and the other people have lawyers and want you to sign, and you don't have a lawyer — walk away. Come back with a lawyer. Because look what happened to me.'"

One of the executives even had the gall to say to her, "Meg, if we had to put a royalty on this for you, those woman you care so much about would not be able to afford it."

The global pregnancy home test kit market is currently valued at around a billion dollars USD a year.

In 2012, an article appeared in the New York Times, giving credit for the home pregnancy test to someone else. "My heart just fell," Crane recalls. She wrote to the Times, even citing her patent numbers, but nobody got back to her. (Eventually, they did, though — and wrote a wonderful article correcting the record. I did not see it at the time.)

All the while, Crane had been keeping the prototype in a shoebox in her closet. One day, the Smithsonian came knocking. "They came to lunch in New York with me," she says. They said they didn't really have money to buy things like this — would she donate it?

Crane declined. She didn't have the money either. She took the device to an auction house. And, lo and behold, the Smithsonian bought it there.

Crane told me that when she first saw that rack of test tubes and thought of the home pregnancy test, she couldn't believe the company wasn't already doing it. To a young woman in the middle of the sexual revolution, it was just so obvious. It's a good reminder to us all: sometimes only the people affected have the perspective we need.

Despite all the creative energy and advocacy she poured into the home pregnancy test, Crane herself never used one. "I was on the pill," she told me.

I have used a few, though. And I'm grateful.

Meg Crane spoke with me, by Zoom and phone, from her home in New York. Many thanks to Rachel Arkell, at the University of Kent, both for the tweet that made me aware of this story and for putting me in touch with Crane.

Related links

Margaret Crane. "Diagnostic Test Device. Patent number 3,579,306." United States Patent Office. 18 May, 1971.

Ed Yong. "How a Frog Became the First Mainstream Pregnancy Test." The Atlantic. 04 May 2017.