Are clinic websites honest about egg freezing?

Women rely on fertility clinic websites for information about egg freezing. New research suggests they shouldn't.

5 minute read

In the beginning, egg freezing was for cancer patients. They risked ruining their eggs during treatment. Young women likely to face premature ovarian failure also froze eggs. But it wasn't long before otherwise healthy women, who weren't in the right situation to start a family, began using it to keep their options open. Now that group dominates.

The idea behind "elective egg freezing" (EEF) is that while your eggs are still youngish and healthy, you should have some removed and put on ice for later. Maybe something about your career will let up and give you a chance to contemplate parenthood. Maybe you'll meet the right partner. Maybe you'll finally have enough money. Maybe you'll just decide it's time.

It's an appealing idea. So much so that, according to the UK's Human Fertilisation and Embryology Authority (HFEA), it's the fastest growing fertility treatment in the country.

If you google "egg freezing," chances are your top hits will be the fertility clinics who sell it. Many women use these clinic websites as their main source of information. But should they? Are clinic websites accurate? Do they provide meaningful information about the procedure? Are they honest about what it will cost?

Zeynep Gurtin and Emily Tiemann, at University College London in the UK, decided to have a look. Below, I report on the findings in their paper, "The marketing of elective egg freezing: A content, cost and quality analysis of UK fertility clinic websites," published in the journal Reproductive Biomedicine and Society Online.

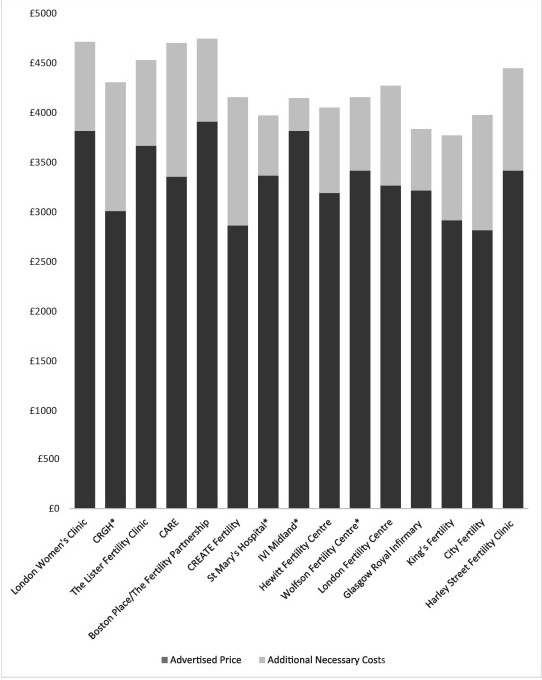

Advertised price for one cycle of elective egg freezing at each clinic, with additional necessary costs added.

Source: Gurtin and Tiemann, 2020

Zeynep Gurtin and Emily Tiemann, at University College London, in the UK, knew that women relied on clinic websites for information about elective egg freezing (EEF). They wanted to see how useful that information was. They were also interested in how clinics marketed the procedure and how transparent they were about cost.

So in June 2019, they downloaded materials about EEF that were on the websites of 15 of the country's fertility clinics. Together, these clinics had performed almost 90 percent of all egg freezing cycles in the decade or so prior to the study.

They evaluated the quality of that online information by asking very pointed questions. Did clinics mention any data from the past three years? Did they give the source for the data they did mention? Did they mention live birth rates? Did they explain the process? Did they explain the risks? The researchers assigned one point for each of ten such quality indicators.

Twelve of the 15 clinics scored two or fewer points — three of them got no points at all. The highest score was just six points out of 10, and only one clinic got that. The researchers admit they were "taken aback" by how poorly clinics scored.

They noted a general absence of data regarding egg freezing success rates. And at times, there were unsubstantiated claims: one clinic, for instance, said (without any references) that a cycle would have a 60 to 80 percent chance of a live birth. The researchers point out this was considerably higher than the 18 percent cited by the HFEA.

The researchers also took issue with the way the procedure was being pitched — as though women were expected to anticipate infertility. "Thus, reproductive ageing is transformed from a natural and inevitable part of the life course, into a liability requiring monitoring and management," they wrote, "and EEF is transformed into a management strategy."

Where risks were mentioned at all, they were usually related to the risk of not being able to have children due to age. Risks of undergoing the procedure were almost completely missing, they found.

Prices, the authors found, were also misleading.

For each of the 15 clinics, they calculated the advertised price of a single cycle of EEF, excluding drugs. Then they emailed or phoned the clinics to confirm exactly what was included in that price.

Egg freezing involves taking drugs to stimulate your ovaries to produce extra eggs, monitoring those eggs as they develop, having the eggs surgically removed and then having them frozen. There are some compulsory steps along the way — scans and blood tests and consultations — but sometimes those costs weren't included in the posted price. One clinic included the price of the egg retrieval, for instance, but left out the price of sedation.

Many clinics were cagey about the costs even when pressed. In four instances, the researchers were unable to ascertain what the price of a single cycle would be, despite multiple direct enquiries.

When the researchers compared the advertised prices to the actual prices, they found that, on average, about a third of the price was not being disclosed on websites. That third amounted to an average of more than £900. (See chart.)

Of course, even that actual price is a gross underestimate of the full cost of using egg freezing to have a child. It doesn't include thawing, for instance, or fertilization — which, after freezing, requires ICSI — and transfer, not to mention years of freezing.

While this is the first study to look at online marketing of egg freezing in the UK, it is not the first study anywhere to do so. A 2014 study of US clinics warned that inadequate information might "encourage women to falsely believe they can indefinitely delay childbearing..." Another US study, in 2017, concluded that websites advertised egg freezing "persuasively, not informatively, emphasizing indirect benefits while minimizing risks and the low chance of successfully bringing a child to term." A Spanish study in 2019 and an Australian study in 2020 also called into question whether websites contained the quality of information needed for a woman to make a well-informed decision.

Gurtin and Tiemann say their results show that "most clinics present an unbalanced view of EEF, do not provide satisfactory information about egg freezing, [and] are not sufficiently clear and transparent about the ‘true’ cost of an EEF cycle…"

The UK Human Fertilitisation and Embryology Authority (HFEA) has the power to license clinics and treatments, but, interestingly, does not have jurisdiction over marketing. Gurtin and Tiemann think that should change, arguing that "it may now be time to consider extending the powers of HFEA to match the growing commercialization of the fertility sector."

*

Zeynep Gurtin and Emily Tiemann. "The marketing of elective egg freezing: A content, cost and quality analysis of UK fertility clinic websites." Reproductive Biomedicine and Society Online. 2020.

*

Note: Sometimes called "social" egg freezing or "non-medical" egg freezing — terms that aren't quite right — the above authors use the words "elective egg freezing," first proposed by Marcia Inhorn, a medical anthropologist at Yale. This is the term I will use from here on.

*

Correction: The publication date for Gurtin and Tiemann’s paper was 2020, not 2021 as originally reported. We regret the error.